By DIANE COWEN

HOUSTON – A sturdy telescope stands tall on a tripod in one corner of Kerry and Angela Stein’s living room, a sign that life in the country is filled with things to see: rainstorms brewing in the distance, wildlife meandering through grassy fields and birds flitting in and out of a small pond or perched in the limbs of sprawling trees.

Photos by Andrew Pogue

The Steins lived in a midcentury-era ranch home on Houston’s west side, and a yearning for land had the couple first looking in the Hill Country, then settling on land closer to Houston since Kerry Stein hasn’t yet retired from his job in the oil and gas industry.

Kerry, a native of San Antonio who grew up visiting his paternal grandfather’s farm in Castroville, knew that someday he’d have his own spread of land, even if farming wasn’t going to be his profession.

Just a few years ago they moved into their modern, minimalist farmhouse, a simple blend of glass and steel, Lueders limestone, and cedar, poplar and pecan woods.

Set back off a farm-to-market road in Washington County between Chappell Hill and Navasota, the low-slug ranch-style home is an odd sight after miles of old-style farmhouses, trailers and traditional, wood-framed homes. Designed by the San Antonio-based Lake Flato architects, the “home” is actually a series of indoor and outdoor spaces, that include what surely is the most eye-catching barn in the region.

They’d never hired an architect or even built a home, but after seeing a couple of homes they liked and finding out that Lake Flato designed both, they knew who their architects would be — even if they didn’t know that much about the award-winning firm at the time.

This 256-acre property is in a new community of small farms known as Gates Ranch — many of which are second homes for Houstonians wanting to get out of the busy city on weekends or easing into semi-retirement. The land was once owned by Amos Gates, a land scout for Stephen F. Austin and part of the Old Three Hundred, the settlers who received land grants in Austin’s first colony back in the 1820s.

In the spring, the Steins’ farm is filled with the purple, pink and yellow of wildflowers, including a small hill covered in bluebonnets. At other times, Stein works hay fields with another farmer, giving his tractor a good workout as he sells 1,500-pound bales of hay to neighbors who raise cattle.

There’s a steady stream of bird life, from a bald eagle who nests nearby and visits to roost in their trees, to ducks, egrets, cranes, roseate spoonbills and even white pelicans who plunk down in their 14-foot-deep pond.

For a handful of years the Steins lived in New Orleans and their home was in a bird sanctuary, so they started learning the species that were all around them. That unofficial hobby has grown to a new level.

“We are, by default, birders now,” quipped Kerry. “The birds were a big surprise. I didn’t expect to see a bald eagle out here. We have a pretty nice spotting scope, and we watched the bald eagle every morning for a few months. He liked to perch in a particular spot and when he’d take flight, all of the ducks would scatter.”

Laura Jensen and Gus Starkey, the Lake Flato project architect and designer, respectively, for the Steins’ home, said projects are borne from the natural features of each location, so a visit to the site started the process.

“Our roots are agrarian and industrial in nature, so this is a homecoming of sorts,” Starkey said. “The firm is really rooted in finding the architecture within the landscape, melding those two together.”

“Our first reaction is always to the site, appreciating the land and trying to identify what’s unique about the property. We wanted to find the right location to take advantage of the lake and give the home an anchor, and a few trees around that pond gave us enough of a moment to tie into,” Starkey continued.

Since the Steins’ 256 acres felt wide open, the goal was for the home to feel that way, too. The main part of the home has a primary bedroom suite, plus an open concept living-dining-kitchen area and a large pantry/laundry room. A carport, then a dogtrot building with two smaller bedroom suites form a courtyard, where the Steins have planted lush zoysia grass, so soft and thick that it’s hard to imagine it’s real grass.

In the distance is that striking barn, covered mostly in corrugated Corten that naturally ages to a rusty red color that you’d expect to see on a traditional, painted barn. It’s where Kerry, a geophysicist, keeps his tractor and his pride and joy: the 1985 Jeep CJ7 that he bought when he graduated from Texas A&M University.

Photos by Andrew Pogue

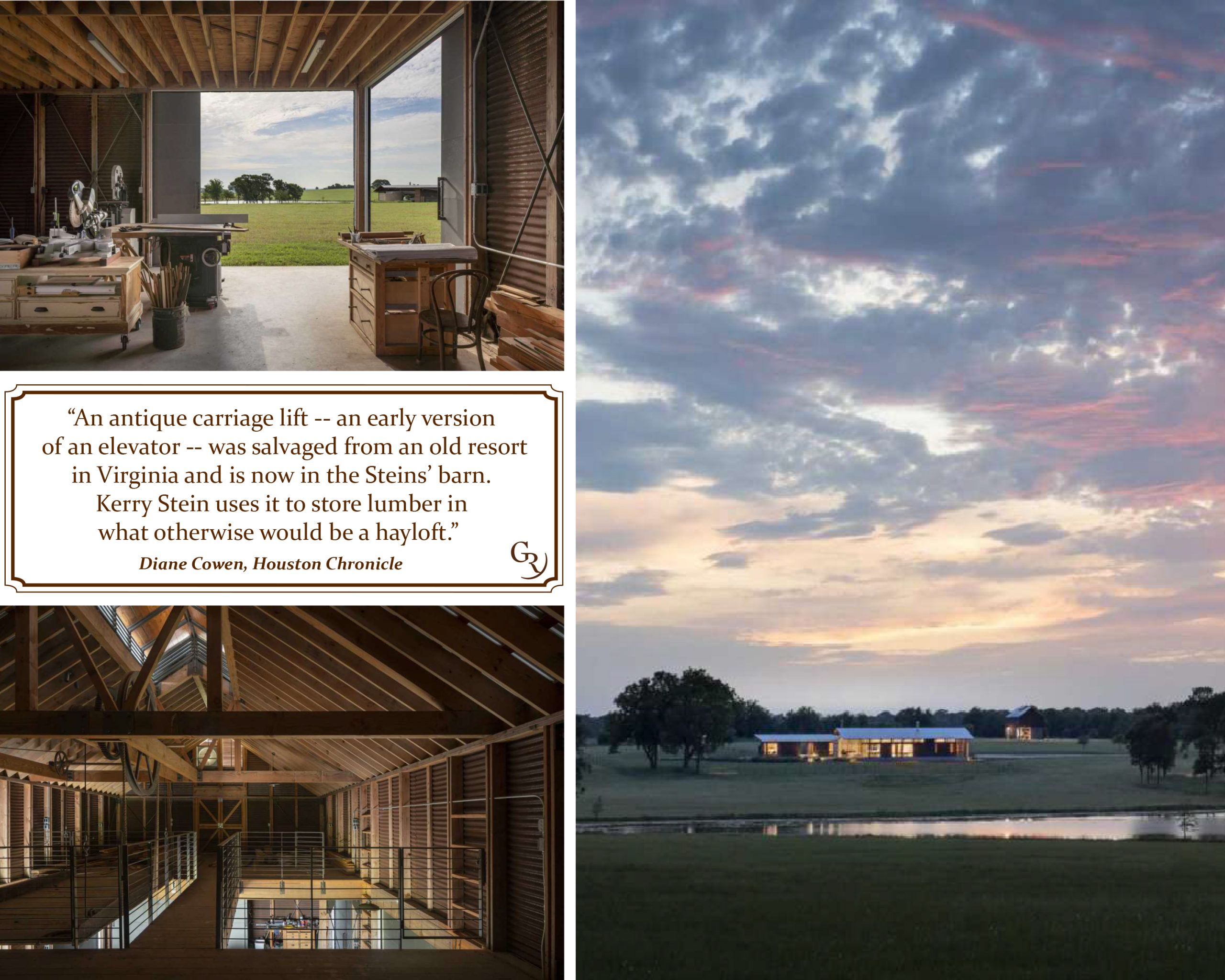

Large sliding panels open up to let natural breezes come through, so Kerry, who enjoys woodworking, can spend hours in his woodshop more comfortably.

There’s a hayloft higher up, but it’s mostly used for storing wood that Kerry uses when making cabinets or other pieces of furniture. And in the center of the barn, mounted in the ceiling beams and rafters, is an unusual steel contraption.

The Steins were watching HGTV’s “Salvage Dawgs,” which chronicles the escapades of the team at Virginia-based Black Dog Salvage as they remove architectural elements from older homes and other structures. In one show they talked about an old carriage lift they’d taken out of the historic Homestead Resort in Hot Springs, Virginia.

More than 250 years ago, vacationers would arrive there to spend the summer in the cooler temperatures of the Allegheny Mountains and their carriages would be stored in a warehouse, heaved to an upper level with a manual lift.

Kerry now jokes that maybe he’d had a little too much wine that night, but he doesn’t regret calling Black Dog Salvage to purchase the lift, and then asking his Lake Flato team to design a barn around it.

It’s a little cumbersome to use — it takes a lot of manpower — so Kerry is working on a counterweight system to make the job a little easier for him to do alone.

And the carport serves a function other than sheltering vehicles. They’re hard to see because of the pitch of the roof, but it’s covered in solar panels that so far have provided all of the electricity the Steins’ home has used.

“A cornerstone of our design perspective is sustainability in all forms and phases,” Starkey said. “We encourage as many clients as possible to include solar panels.”

At a glance, the home appears to have a roof that hovers above the structure, an illusion prompted by a series of clerestory windows that wrap around much of the home. Inside, that upper level has exposed steel trusses that visually form criss-crosses through the length of the home.

In the main house, Lueders limestone was used around the fireplace and on the walls of the kitchen. Smooth slabs of it serve as counters in the pantry, kitchen and bathrooms.

Kerry bought wood from old boxcars and shaped it together to create a giant cutting-board style top for the large kitchen island. Other wood in the home includes poplar in the cabinets, which Kerry made himself over the course of about a year, working on it evenings and weekends.

The pecan wood floors came from a huge tree that fell on Kerry’s grandfather’s farm, so every time he looks at them he remembers the joys of being outdoors on the farm.

At one end of the living room are four glass panels. One a door that can open wide and the other three that fold up accordion style so that the living room and the covered outdoor patio seem as one.

A pretty blue swimming pool provides fun for their 19 nieces and nephews, and the Steins fire up their outdoor pizza oven when his big, extended family visits. It takes about 90 minutes to get hot enough, but then it takes just 90 seconds to bake a pie.

A small orchard of olive trees is still maturing, but when they start producing fruit the couple will either learn to brine them or find a press to extract their own olive oil.

For now, they appreciate the view from their living room, a picture perfect sunrise every single day.

To view the full article, please click here.